Clusiidae

Owen Lonsdale and Steve Marshall

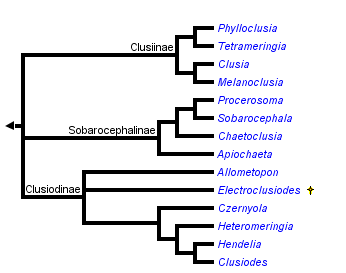

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

A specimen of Chaetoclusia sabroskyi (Soos) showing partially infuscated wings and typical clusiid antennae. Click on the image to take a closer look. Image © Owen Lonsdale

The Clusiidae are a family of small, thin, yellow to black flies with the wing usually partially infuscated. The antenna most readily diagnoses the family: the outer and (sometimes) inner distal margins of the pedicel have a triangular extension, and the arista is dorsoapical (separating it from most other acalyptrate families) on an (frequently) orbicular first flagellomere.

As adults are often encountered as solitary figures in old growth deciduous forests, they have been given the common name "druid flies". The term lekking fly might also apply, but this may be misleading as true lekking has only been found in one of the three subfamilies.

Adults are uncommonly collected in the field, but they can be relatively abundant in some microhabitats. Small dung baits and Malaise traps have been the most successful methods of collection, but a number of species have been swept from grass or collected off of foliage, logs and dead patches of wood on standing trees. North American adults appear to prefer mixed and deciduous forests sometimes associated with grass-dominated areas. Tropical species have often been collected along waterways in mossy, humid habitats (Lonsdale & Marshall, 2010). Clusiids have been known to feed on nectar, rotting vegetative matter, sap (Soós 1987), and the dung of birds and mammals.

The Clusiidae are one of a handful of acalyptrate families known to engage in lekking behaviour. Males establish dominance in a lekking site by defending territories (devoid of resource) from other males on logs or branches in order to attract females and mate. After mating, clusiid females lay eggs elsewhere, usually under bark or in wood in a state of more advanced decay than the surface used for lekking (Rohácek 1995). The wood likely provides a moist environment with an adequate supply of saprobes for feeding larvae. Selection of clusiid oviposition sites does not appear to be associated with any particular species of tree, but is limited by "humidity, amount of shade, stage of wood decay, [and the] presence of mycelia of certain fungi" (Rohácek 1995). Larvae of Sobarocephala occur in the same environment as the adults, and have been found only within decaying wood and termite colonies (Sóos 1987). Malloch (1918) also found the larvae of S. flaviseta to be "evidently associated with the burrows of coleopterous insects" and to be relatively sluggish and slow moving.

Hendelia kinetrolikros. © Steve Marshall

Males of some clusiids, particularly Hendelia Czerny, have enlarged heads or other conspicuous modifications used in mutual assessment on lek sites (see photos above and below) (McAlpine 1976, Marshall 2000). Sobarocephala latipennis Melander & Argo and several Australian Hendelia have strongly widened heads, and Hendelia kinetrolicros (Caloren & Marshall) (pictured above), Hendelia mirabilis (Frey), and Procerosoma alini (Shatalkin) have spectacular long genal processes that are probably used in male-male agonistic interactions, although these species have never been observed while engaged in such behavior (Lonsdale & Marshall, 2010).

Heteromeringia nitida males facing off in a territorial dispute. Image © Steve Marshall

Characteristics

Head of Clusiodes johnsoni Malloch; (ar) arista, (fr orb) fronto-orbital bristle, (if) interfrontal bristle, (oc) ocellar bristle, (pv) postvertical bristle, (vb) vibrissae. Drawing © Owen Lonsdale.

Clusiids are slender acalyptrate flies (usually) 2.5-6.0 mm in length, most readily identified by an angulate extension on the outer margin of the pedicel, a dorsoapical arista (dorsobasal in similar families) on an orbicuar first flagllomere, a complete subcosta, one subcostal break, one pair of vibrissae, and five or fewer fronto-orbital bristles. Most species are yellow with a brown to black pattern, but several species are entirely pale (some Sobarocephala Czerny), and a number of taxa are predominantly brown to black (many Heteromeringia Czerny and Czernyola Bezzi).

There are three to five (sometimes two) fronto-orbital bristles; the anterior bristle is sometimes inclinate, and if there are four or five fronto-orbitals, the third from the back is sometimes inclinate and proclinate (Czernyola). Convergent interfrontal bristles are sometimes present. The ocellar and postvertical bristles are divergent and usually small to absent. On the thorax, there are one to three dorsocentral bristles, one postpronotal, two notopleurals, two or three intra-alars (the presutural intra-alar is sometimes absent), one or two intra post-alar bristles, and one strong anepisternal and katepisternal bristle; a presutural intra-alar and/or a prescutellar acrostichal is sometimes present. The mid and hind tibiae sometimes have one or two dorsal preapical bristles. The subcosta is complete and a subcostal break is present, although this break is indistinct in most Clusiodinae (Lonsdale & Marshall, 2010).

Eggs are translucent, usually three to four times longer than wide, and approximately as long as sternite 6 of the female (Lonsdale & Marshall, 2010). Both ends are tapered (most pronounced anteriorly) and the micropyle is small and terminal. The surface of the egg is minutely tuberculate with (usually) no more than a dozen longitudinal wrinkles. In Sobarocephala, these wrinkles are bordered by larger quadrate tubercles, and some of the wrinkles are branched.

Larvae are known from European Clusiodes Coquillett. The cephalic papillae are minute, the mandibles are small and well sclerotized, and the cephalopharyngeal skeleton is vestigial and unpigmented (Soós, 1987). The anterior spiracles have six openings, each on a small raised tubercle (Soós, 1987). The posterior spiracles are elevated on chitinized plates, produced as dorsally curving hooks with three elongate-oval openings on the medial or ventral half (Malloch, 1918). The anal plate is large, heavily sclerotized, wider than long and tapered laterally (Malloch, 1918).

Puparia (known from temperate Clusia Haliday, Sobarocephala and Clusiodes) are brownish-orange in colour and covered with numerous minute transverse wrinkles (Lonsdale & Marshall, 2010). The posterior face is smooth with various sculpturing, and either sharply curved and bordered by a high ridge (Clusia and Sobarocephala), or broadly rounded with the ridge broken and shallow (Clusiodes). The anal hooks curve dorsally (Clusiodes) or dorsomedially, and are ovate (Clusia) or semi-circular (Sobarocephala) in cross-section.

Figure: Immature stages clockwise from left: egg, Clusiodes pictipes (Zetterstedt); puparium (posterior face), Clusiodes johnsoni Malloch; puparium (posterior face), Clusiodes melanostomus (Loew); puparium (posterior face), Clusia occidentalis Malloch; puparium (dorsal - posterior third), Clusia occidentalis; puparium (lateral) Clusiodes johnsoni. © Owen Lonsdale.

Externally, clusiid male genitalia are composed of a dome-shaped epandrium, well developed surstyli, two cerci that are confluent basally, and an 'annulus' comprised of sternites 6-8 (Lonsdale & Marshall, in press). Internally, the genitalia are made up of a subepandrial sclerite, a hypandrium with three lateral setae and a pair of 'arms' that attach to the subepandrial sclerite, a rod-like phallapodeme, a ring-like basiphallus, a fin-like epiphallus, a short to long distiphallus, one pair of lateral lobes at the base of the distiphallus, a single ejaculatory apodeme, and one pair of pregonites and postgonites. This ground-plan is highly modified in the Clusiodinae excluding Allometopon Kertesz, as the postgonite, epiphallus, and lateral lobes of the distiphallus are absent, the pregonite is enlarged and fused to the hypandrium, the phallapodeme is short and variably modified, and the hypandrial arms are partly attached to the annulus (Lonsdale & Marshall, 2006). The phallus itself may also be highly modified, being either large and sac-like, extremely long and coiled, or atrophied to absent.

Figure. Top left: Sobarocephala latifrons male terminalia, left lateral (hypandrial complex shaded); centre: Sobarocephala latifrons hypandrial complex; Clusiodes johnsoni hypandrial complex. © Owen Lonsdale.

The female genitalia are much simpler than those of the male, being comprised of a ventral receptacle and one pair of spermathecae. These structures are weakly sclerotized and difficult to examine, and staining is often necessary. In the Clusiinae and Sobarocephalinae, the spermathecae are often simple and spherical, but in the Clusiodinae, they are longitudinally segmented and sometimes telescoped and heavily pigmented. The ventral receptacle is usually sac-like and recurved, but this generalized form is variably modified in several genera.

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

Clusiinae & Clusiodinae: Early hypotheses. Frey (1960) divided the Clusiidae into two subfamilies, Clusiodinae (characterized by reclinate fronto-orbital bristles) and Clusiinae (with at least one pair of inclinate fronto-orbital bristles). Subsequent authors, including Steyskal (1965), Soós (1987), Sasakawa (1977) and Pitkin & Evenhuis (1989) restricted the Clusiinae to those genera with only the anterior fronto-orbital bristle inclinate, moving Czernyola to the Clusiodinae.Sobarocephalinae. During the development of genus-level revisions by Lonsdale & Marshall, it became evident that neither of the existing subfamily concepts based on head chaetotaxy corresponded with clades defined by synapomorphies of the male and female genitalia, as well as previously unrecognized external morphological characters. As such, an alternate three-subfamily hypothesis based on morphological synapomorphies was proposed to better reflect the evolutionary history of the group. Lonsdale & Marshall (2006) redefined the Clusiinae and Clusiodinae on the basis of these derived characters, and described the new subfamily Sobarocephalinae. This new subfamily contained Sobarocephala and Chaetoclusia, which were previously treated as Clusiinae, and the new genus Procerosoma Lonsdale & Marshall.

Molecular Evidence - transfer of Apiochaeta to the Sobarocephalinae. The first full phylogenetic hypothesis of the Clusiidae was presented by Lonsdale et al. (2010), which included not only the morphological characters used in Lonsdale & Marshall (2006) and their subsequent generic revisions, but molecular sequence data from a number of genes. These genes were analyzed separately, in combination with each other and with the morphological data set. An illustrated hypothesized development of the male and female genitalic characters was also provided, along with an updated genus key.

The results of the analyses were largely unsurprising, as they provided strong support for most existing sister-group relationships within the family and provided little support for basal branches. One striking finding was revealed, however: the genus Apiochaeta, while having a morphological affinity to Clusia, was in fact strongly allied to the Sobarocephalinae, illustrating an incredible example of character reversal and convergence in a single clusiid lineage. As such, this Chilean genus was included in a redefined Sobarocephalinae, which now contained all endemic New World clusiid genera. In contrast, the Clusiinae and Clusiodinae appear to have originated in the Old World, which made the former's inclusion of Apiochaeta problematic biogeographically.

Examining the new cladistic evidence, the redefined Clusiodinae (containing Allometopon, Clusiodes, Czernyola, Hendelia, Heteromeringia, and the fossil genus Electroclusiodes Hennig) is supported by longitudinally segmented spermathecae, loss of the ventrolateral lobes of the hypandrium, entirely reclinate fronto-orbital bristles and loss of the presutural intra-alar bristle. An inclinate anterior fronto-orbital is recovered in Heteromeringia, which had previously allied it to the Clusiinae.

The New World subfamily Sobarocephalinae includes the south temperate Apiochaeta, the large, primarily neotropical genus Sobarocephala and two small, closely related neotropical genera (Chaetoclusia Coquillett and Procerosoma). The Sobarocephalinae, while strongly supported on the basis of molecular evidence, is poorly-supported morphologically, defined by a ventrolateral lobe of the hypandrium that is usually at least as long as the hypandrial arm (secondarily reduced in several species of Chaetoclusia and Sobarocephala), and a relatively large surstylus. The neotropical lineage (ie. the subfamily excluding Apiochaeta) is much better supported on the basis of male genitalic characters.

The Clusiinae includes the small genera Phylloclusia Hendel and Tetrameringia McAlpine that are primarily distributed around the Indian Ocean, the monotypic Melanoclusia Lonsdale & Marshall from Borneo, and the Holarctic and Oriental genus Clusia (Lonsdale & Marshall, 2006, 2008). The subfamily is better supported than the Sobarocephalinae, defined by loss of the mid tibial and hypandrial bristles, and a medially broken distiphallus. Most of the characters used to define the subfamily in Lonsdale & Marshall (2006) are also found in Apiochaeta, and therefore now interpreted as ancestral states of both the Clusiinae and the Sobarocephalinae: a small ratio of the length of the ultimate section of vein M to the penultimate, outstanding bristles on the posterodorsal surface of the fore femur, a bent or jointed distiphallus, and a posteromedial truncated notch on the vertex.

References

Frey, R. 1960. Studien über indoaustralische Clusiiden (Dipt.) nebst Katalog der Clusiiden. Commentationes Biologicae. 22(2): 1-31.

Lonsdale, O. & Marshall, S.A. 2006. Redefinition of the Clusiinae and Clusiodinae, description of the new subfamily Sobarocephalinae, revision of the genus Chaetoclusia and a description of Procerosoma gen. n. (Diptera: Clusiidae). European Journal of Entomology, 103: 163-182.

Lonsdale, O. & Marshall, S.A. 2008. Synonymy within Clusia and description of the new genus Melanoclusia (Diptera: Clusiidae: Clusiinae). Ann. Ent. Soc. Am. 101(2): 327-330.

Lonsdale, O. & Marshall, S.A. 2010. 78: Clusiidae. Pp. 1041-1048, In: Brown, B. et al. (Eds.) "Manual of Central American Diptera, Volume 2". NRC Research Press, Ottawa.

Lonsdale, O., Marshall, S.A., Fu, J. & Wiegmann, B. 2010. Phylogenetic analysis of the druid flies (Diptera: Schizophora: Clusiidae) based on morphological and molecular data. Insect Systematics & Evolution 41: 231-274.

Malloch J.R. 1918: A revision of the dipterous family Clusiodidae (Heteroneuridae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 20(1): 2-8.

Marshall, S.A. 2000. Agonistic behaviour and generic synonymy in Australian Clusiidae (Diptera). Studia Dipterologica. 7: 3-9.

McAlpine, D.K. 1976. Spiral vibrissae in some clusiid flies (Diptera: Schizophora). Australian Entomological Magazine. 3(4): 75- 78.

Pitkin, B.R. & N.L. Evenhuis. 1989. Family Clusiidae. In N.L. Evenhuis (editor). Catalog of the Diptera of the Australasian and Oceanian regions. Pp. 534-536. Bishop Museum Press & E.J. Brill, Honolulu.

Sasakawa, M. 1977. Family Clusiidae. In M.D. Delfinado & D.E. Hardy (editors). A catalog of the Diptera of the Oriental region. Pp. 234-239. University Press of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Steyskal, G.C. 1965. Family Clusiidae. In Stone et al. (eds.). A catalogue of the Diptera of America north of Mexico. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Washington, D.C.

Rohácek, J. 1995. Clusiidae (Diptera) of the Czech and Slovak Republics: Faunistics and notes on biology and behaviour. Casopis Slezského Muzea Opava. (A) 44: 123-140.

Sóos A. 1987: Clusiidae McAlpine J.F. (ed.): Manual of Nearctic Diptera, Vol. 2. Monograph 28, Research branch, Agriculture Canada, Ottawa Pp. 853-857.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Hendelia gladiator (McAlpine) |

|---|---|

| Location | Australia |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Sex | Male |

| Copyright |

© 2004 Steve Marshall

|

| Scientific Name | Apiochaeta limbipennis |

|---|---|

| Location | Chile |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Sex | Female |

| Life Cycle Stage | Adult |

| Copyright |

© Steve Marshall

|

| Scientific Name | Clusiodes ater Melander & Argo |

|---|---|

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Life Cycle Stage | Adult |

| Copyright |

© Steve Marshall

|

About This Page

Owen Lonsdale

Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids & Nematodes

Steve Marshall

University of Guelph, Canada

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Owen Lonsdale at and Steve Marshall at

Page copyright © 2011 Owen Lonsdale and Steve Marshall

Page: Tree of Life

Clusiidae.

Authored by

Owen Lonsdale and Steve Marshall.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Clusiidae.

Authored by

Owen Lonsdale and Steve Marshall.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- First online 10 December 2004

- Content changed 06 January 2011

Citing this page:

Lonsdale, Owen and Steve Marshall. 2011. Clusiidae. Version 06 January 2011. http://tolweb.org/Clusiidae/10628/2011.01.06 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site