Pezizomycotina

Joey Spatafora

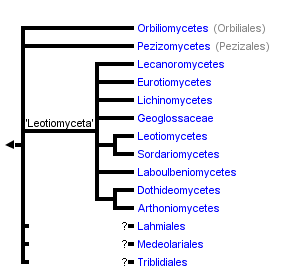

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

Pezizomycotina is the largest subphylum of Ascomycota with more than 32,000 described species (Kirk et al. 2001). It approximately equates to Ascomycetes sensu Kirk et al. 2001 and Euascomycetes sensu Alexopoulos et al. 1996, and it includes all filamentous, sporocarp-producing species, with the exception of Neolecta of Taphrinomycotina (Sugiyama et al. 2006). Pezizomycotina is ecologically diverse with species functioning in ecological processes and symbioses including wood and litter decay, animal and plant pathogens, mycorrhizae, endophytes and lichens, and occurring in aquatic and terrestrial habitats (Spatafora et al. 2006).

Pezizomycotina includes numerous species that impact humans in both beneficial and detrimental ways (Alexopoulos et al. 1996). Medically important species have been the source of both disease (e.g., Coccidioides immitis – Valley Fever) and life saving drugs (e.g., Penicillium chrysogenum – penicillin, Tolypocladium inflatum - Cyclosporin A). Introduction of some invasive species have forever altered native forests (e.g., Cryphonectria parasitica - Chestnut Blight, Ophiostoma ulmi – Dutch Elm Disease), while around 40% of the species form lichens (e.g., Lecanoromycetes) that cover up to 8% of the earth surface and are major sources of fixed carbon in terrestrial environments. Species of Pezizomycotina also have prominent industrial applications including production of organic acids (e.g., Aspergillus niger – citric acid) and enzymes and fermented foods (e.g., Aspergillus oryzae – amylase, soy sauce).

Characteristics

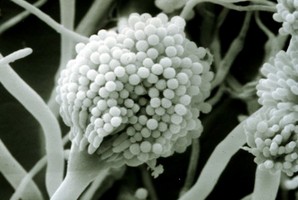

Most species of Pezizomycotina produce a dominant filamentous or hyphal growth phase, although several species are known to be dimorphic, growing as unicellular budding yeasts under certain conditions. The hyphae of Pezizomycotina are regularly septate with a simple septum that possesses a single pore dividing the hyphae into hyphal compartments or “cells” (Fig. 1; Momany et al. 2002). Associated with the septum of Pezizomycotina is the Woronin body (Fig. 1). It is a specialized vesicle that functions to seal the septal pore in response to cellular damage and is comprised of HEX-1 protein that self-assembles to form the solid core of the vesicle (Jedd & Chua, 2000; Tenney et al. 2000). The “cells” of most Pezizomycotina possess a single haploid nucleus, although numerous exceptions to this condition exist.

From left to right: Fig. 1. Hyphal septum with Woronin Bodies. Aspergillus. © M. Momany and E. Richardson. Fig. 2. Ascus with ascospores. Dothidea © S. Huhndorf. Fig. 3. Mature conidiophores. Aspergillus © C.W. Mims

As discussed for Ascomycota, the life cycles of Pezizomycotina are highly pleomorphic, with a single species producing 0-1 meiospore-producing stages and 0-many mitospore-producing stages. The meiotic phase (teleomorph) involves the fertilization of a female gametangium (ascogonium) by either a male gametangium (antheridium) or a male gamete (spermatium or microconidium). Fertilized ascogonia develop into dikaryotic ascogenous hyphae, which ultimately develop into asci. Asci are the site of meiosis and meiospore (ascospore) production (Fig. 2). The mitotic phase (anamorph) involves the production of mitotic propagules with the most frequent being the production of mitospores (conidia) from specialized conidiogenous cells (Fig. 3). Connections between teleomorphs and anamorphs of the same species are frequently unknown as the two often do not co-occur in time (e.g., seasons) and/or space (e.g., host). Thus, as a matter of convenience the International Botanical Code allows unique Latin binomials for both the teleomorph and anamorph with the teleomorph name taking priority. For example, the Aspergillus nidulans is the anamorph of the teleomorph Emericella nidulans.

Sporocarp and Meiosporangium Diversity

The four main ascomal or sporocarp morphologies include apothecia, perithecia, cleistothecia and ascostromata (Alexopoulos et al. 1996). Apothecia are typically disc-shaped to cup-shaped to spathulate in morphology and produce asci in a well-defined layer, a hymenium, exposed to the environment (Fig. 4). Perithecia (Fig. 5) and cleistothecia (Fig. 6) are partially or completely enclosed ascomata, respectively, with ascus production occurring within the central cavity of the ascoma. These three ascomal types are generally presumed to develop after fertilization of the ascogonium (female gametangium). Ascostromata differ in that asci are formed in preformed locules (ascolocular development; Nannfeldt 1932, Luttrell 1973), which often develop in flask shaped (pseudothecia) or open, cup shaped (hysterothecia and thyriothecia) stromatic tissue that superficially resemble perithecia or apothecia, respectively (Fig. 7). It is generally presumed that initiation of ascostromata development occurs prior to fertilization of ascogonia.

From left to right: Fig. 4. Apothecia of Aleuria. © J.H. Petersen/MycoKey. Fig. 5. Perithecia of Neurospora. © N.B. Raju. Fig. 6. Cleistothecia of Eupenicillium. © D. Geiser. Fig. 7. Ascostroma of Tubeufia. S. Huhndorf.

The major ascus types include operculate, inoperculate, prototunicate, unitunicate and bitunicate, which are based primarily on the number and thickness of functional ascus walls and mechanisms of dehiscence (Eriksson 1981, Alexopoulos et al. 1996, Kirk et al. 2001). Operculate asci are restricted to apothecial fungi of Pezizomycetes (Fig. 8). They release their ascospores through a defined operculum that is either formed terminally or subterminally at the ascus apex. Inoperculate asci are produced by apothecial (Lecanoromycetes, Leotiomycetes, Orbiliomycetes), cleistothecial (Sordariomycetes, Leotiomycetes) and perithecial (Sordariomycetes) fungi and are typically thin-walled and release their spores through a pore or canal, by rupturing of the ascus apex, or by disintegration of the ascus wall (Fig. 9). Prototunicate asci are produced by apothecial (Lecanoromycetes), cleistothecial (Eurotiomycetes) and perithecial (Sordariomycetes) fungi. They are thin-walled, typically globose to broadly clavate, and release their ascospores passively by disintegration of the ascus wall (Fig. 10). Bitunicate asci are conspicuously thick-walled and characterized by possessing two, often separable, functional ascus walls, the exotunica and endotunica (Fig. 11). They are produced by ascostromatic lichenized and nonlichenized species (Dothideomycetes, Eurotiomycetes) and ascohymenial lichens (Arthoniomycetes). In the traditional definition of bitunicate asci, ascus dehiscence occurs when the endotunica ruptures through the exotunica in a “jack-in-the-box” manner (Eriksson 1981). Additional modes of dehiscence exist among “bitunicate” ascus morphologies that involve little to no ascus wall separation (e.g., Lecanoromycetes; Eriksson 1981, Hafellner 1988). Due to the nonfissitunicate mechanisms of dehiscence and relatively thin ascus walls, operculate, inoperculate, and prototunicate asci are collectively referred to as unitunicate (Luttrell 1951).

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

Prior to molecular phylogenetics, classifications of sporocarp-producing Ascomycota were based on varying interpretations of morphology and development of ascomata (sporocarps) and asci (meiosporangia). The major taxa and associated character states were: Discomycetes – apothecia, operculate and inoperculate asci; Pyrenomycetes – perithecia, inoperculate asci; Plectomycetes – cleistothecia, prototunicate asci; and Loculoascomycetes – ascostromata, bitunicate asci (reviewed in Alexopoulos et al. 1996). Multigene phylogenetic analyses rejected this classification scheme and supported the existence of at least 10 major clades of Pezizomycotina (Spatafora et al. 2006). These studies reveal that apothecia are likely plesiomorphic for the subphylum and that most major ascomal and ascal character states (e.g., cleistothecia and prototunicate asci) have been gained and lost several times.

The two earliest diverging lineages of Pezizomycotina are Orbiliomycetes and Pezizomycetes. Both taxa produce apothecial ascomata but are distinguished by Pezizomycetes producing operculate asci (Hansen & Pfister 2006) and Orbiliomycetes producing small, inoperculate asci. Current analyses cannot distinguish between either class being the earliest diverging lineage of the Pezizomycotina. The remaining classes of the Pezizomycotina form a well-supported superclass taxon that is informally referred to as ‘Leotiomyceta’. Classes of ‘Leotiomyceta’ include Arthoniomycetes, Dothideomycetes (Schoch et al. 2006), Eurotiomycetes (Geiser et al. 2006), Laboulbeniomycetes, Lecanoromycetes (Miadlikowska et al. 2006), Leotiomycetes (Wang et al. 2006), Lichinomycetes, and Sordariomycetes (Ning et al. 2006). Superclass relationships among these taxa are mostly unresolved with the exception of the sister group relationships of Arthoniomycetes and Dothideomycetes, and Leotiomycetes and Sordariomycetes, respectively. Geoglossaceae was classified in the Leotiomycetes, but is strongly rejected as a member of the class. It is currently classified ‘Leotiomyceta’ incertae sedis and may form a clade with Lichinomycetes or represent another class-level lineage.

References

Alexopoulos, CJ, Mims, CW, Blackwell, M. 1996. Introductory Mycology, 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons, New York, New York, USA.

Eriksson, OE. 1981. The families of bitunicate Ascomycetes. Opera Botanica 60: 1-209.

Geiser, D.M., Gueidan, C., Miadlikowska, J., Lutzoni, F., Kauff, F., Hofstetter, V., Fraker, E., Schoch, C.L., Tibell, L., Untereiner, W., and Aptroot, A. 2006. Eurotiomycetes: Eurotiomycetidae and Chaetothyriomycetidae. Mycologia 98: 1053-1064.

Hafellner, J. 1988. Priniciples of classification and main taxonomic groups, In CRC Handbook of Lichenology (M. Galun, ed.) 3: 4-52, CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Hansen, K. and Pfister, D.H. 2006. Systematics of the Pezizomycetes – the operculate discomycetes. Mycologia 98: 1029-1040.

Hibbett, D. S., M. Binder, J. F. Bischoff, M. Blackwell, P. F. Cannon, O. E. Eriksson, S. Huhndorf, T. James, P. M. Kirk, R. Lücking, T. Lumbsch, F. Lutzoni, P. B. Matheny, D. J. Mclaughlin, M. J. Powell, S. Redhead, C. L. Schoch, J. W. Spatafora, J. A. Stalpers, R. Vilgalys, M. C. Aime, A. Aptroot, R. Bauer, D. Begerow, G. L. Benny, L. A. Castlebury, P. W. Crous, Y.-C. Dai, W. Gams, D. M. Geiser, G. W. Griffith, C. Gueidan, D. L. Hawksworth, G. Hestmark, K. Hosaka, R. A. Humber, K. Hyde, J. E. Ironside, U. Kõljalg, C. P. Kurtzman, K.-H. Larsson, R. Lichtwardt, J. Longcore, J. Miądlikowska, A. Miller, J.-M. Moncalvo, S. Mozley-Standridge, F. Oberwinkler, E. Parmasto, V. Reeb, J. D. Rogers, C. Roux, L. Ryvarden, J. P. Sampaio, A. Schüßler, J. Sugiyama, R. G. Thorn, L. Tibell, W. A. Untereiner, C. Walker, Z. Wang, A. Weir, M. Weiß, M. M. White, K. Winka, Y.-J. Yao, and N. Zhang. 2007. A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi. Mycological Research 111: 509-547.

Jedd, G., and Chua, N. H. 2000. A new self-assembled peroxisomal vesicle required for efficient resealing of the plasma membrane. Nat. Cell Biol. 2: 226 –231.

Kirk, PM, Cannon, PF, David, JC, Stalpers, JA. 2001. Ainsworth and Bisby’s Dictionary of the Fungi, 9th ed. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Luttrell, ES. 1951. Taxonomy of the Pyrenomycetes. Univ. Missouri Stud. 3: 1-120.

Luttrell, ES. 1973. Loculoascomycetes. Pp. 135-219. In: The Fungi, Vol. IVA. Eds. G. C. Ainsworth, F. K. Sparrow, and A. S. Sussman. Academic, New York.

Lutzoni, F., F. Kauff, C. J. Cox, D. McLaughlin, G. Celio, B. Dentinger, M. Padamsee, D. Hibbett, T. Y. James, E. Baloch, M. Grube, V. Reeb, V. Hofstetter, C. Schoch, A. E. Arnold, J. Miadlikowska, J. Spatafora, D. Johnson, S. Hambleton, M. Crockett, R. Shoemaker, G.-H. Sung, R. Lücking, T. Lumbsch, K. O’Donnell, M. Binder, P. Diederich, D. Ertz, C. Gueidan, K. Hansen, R. C. Harris, K. Hosaka, Y.-W. Lim, B. Matheny, H. Nishida, D. Pfister, J. Rogers, A. Rossman, I. Schmitt, H. Sipman, J. Stone, J. Sugiyama, R. Yahr, and R. Vilgalys. 2004. Assembling the fungal tree of life: progress, classification, and evolution of subcellular traits. American Journal of Botany 91: 1446–1480.

Miadlikowska, J., Kauff, F., Hofstetter, V., Fraker, E., Grube, M., Hafellner, J., Reeb, V., Hodkinson, B.P., Kukwa, M., Lücking, R., Hestmark, G., Otalora, M.G., Rauhut, A., Büdel, B., Scheidegger, C., Timdal, E., Stenrros, S., Brodo, I., Perlmutter, G.B., Ertz, D., Diederich, P., Lendemer, J.C., May, P., Schoch, C.L., Arnold, A.E., Gueidan, C., Tripp, E. Yahr, R., Robertson, C., and F. Lutzoni. 2006. New insights into classification and evolution of the Lecanoromycetes (Pezizomycotina, Ascomycota) from phylogenetic analyses of three ribosomal RNA- and two protein-coding genes. Mycologia 98: 1088-1103.

Momany. E., Richardson, E.A. and Sickle, C.V. 2002. Mapping Woronin body position in Aspergillus nidulans. Mycologia 94: 260-266.

Nannfeldt, JA. 1932. Studien über die Morphologie und Systematik der Nicht-Lichenisierten Inoperculaten Discomyceten. Nova Acta Regiae Soc. Sci. Upsal. IV 8:1-368.

Schoch, C.L., Shoemaker, R.A., Seifert, K.A., Hambleton, S., Spatafora, J.W., Crous, P.W. 2006. A multigene phylogeny of the Dothideomycetes using four nuclear loci. Mycologia 1043-1054.

Spatafora, J.W., Johnson, D., Sung, G.-H., Hosaka, K., O’Rourke, B., Serdani, M., Spotts, R., Lutzoni, F., Hofstetter, V., Fraker, E., Gueidan, C., Miadlikowska, J., Reeb, V., Lumbsch, T., Lücking, R., Schmitt, I., Aptroot, A., Roux, C., Miller, A., Geiser, D., Hafellner, J., Hestmark, G., Arnold, A.E., Büdel, B., Rauhut, A., Hewitt, D., Untereiner, W., Cole, M.S., Scheidegger, C., Schultz, M., Sipman., H. and Schoch, C. 2006. A five-gene phylogenetic analysis of the Pezizomycotina. Mycologia 98: 1020-1030.

Sugiyama, J., Hosaka, K. and Suh, S.-O. 2006. Early diverging Ascomycota: phylogenetic divergence and related evolutionary enigmas. Mycologia 98: 996-1005.

Tenney, K., Hunt, I., Sweigard, J., Pounder, J.I., McClain, C., Bowman, E.J., and Bowman, B.J. 2000. hex-1, a Gene Unique to Filamentous Fungi, Encodes the Major Protein of the Woronin Body and Functions as a Plug for Septal Pores. Fun. Gen. & Biol. 31: 205-217.

Weng, Z., Johnston, P.R., Takamatsu, S., Spatafora, J.W., and D. Hibbett. 2006. Toward a phylogenetic classification of the Leotiomycetes based on rDNA data. Mycologia 98: 1065-1075.

Zhang, N., Castlebury, L.A., Miller, A.N., Hundorf, S.M., Schoch, C.L., Seifert, K.A., Rossman, A.Y., Rogers, J.D., Kohlmeyer, J., Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B., and G.-H. Sung. 2006. An overview of the systematics of the Sordariomycetes based on a four-gene phylogeny. Mycologia 98: 1076-1087.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Cordyceps |

|---|---|

| Body Part | thallus erupting from moth |

| Copyright |

© Joey Spatafora

|

| Scientific Name | Helvella lacunosa |

|---|---|

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Source | helvella lacunosa |

| Source Collection | Flickr |

| Image Use |

This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 2.0. This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 2.0.

|

| Copyright | © 2008 MAVI RODRIGUEZ GARCIA |

About This Page

Joey Spatafora

Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Joey Spatafora at

Page copyright © 2007 Joey Spatafora

All Rights Reserved.

- First online 09 October 2006

- Content changed 19 December 2007

Citing this page:

Spatafora, Joey. 2007. Pezizomycotina. Version 19 December 2007. http://tolweb.org/Pezizomycotina/29296/2007.12.19 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site